In his book, Open Sky, Paul Virilio gives an often bleak and unflattering commentary on how technology is affecting our social interactions, needs, and even our accidents. on page 2 of the introduction, he makes a statement that serves as a pretty apt summation of the entire book, saying:

|

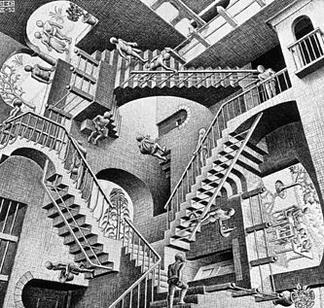

| M.C. Escher's famous piece, Relativity. |

Virilio speaks of two intervals that have affected humanity's cognitive history, therefore shaping our historical perception of reality. The first of these intervals is time (duration). By observing the flow of time in the natural world--day length, seasonal changes, annual time, etc.--man situates himself as a time-bound being. Our observance of and adherence to time shapes the way we see ourselves as well as the things we do. Likewise with the second interval, space. In the interval of space, man situates and measures himself by a system of geographic relativism. Space (essentially, distance) affects the way we construct physical reality. Virilio proposes a third interval, that of time-light (14). Time-light, what Virilio refers to as the "absolute standard for immediate action, for instantaneous teleaction" (14), is what creates our current world where everything is a general accident.

In a world that habitually celebrates technology and it's proposed benefit to our lives, Paul Virilio serves as a counterbalance, delivering a bleak and sometimes alarmist take on communication technology and the internet. We are a world society obsessed with technology. Except for isolated indigenous people, I think it's impossible to say that there's not a single person on the planet that doesn't use or benefit from technology (and even that's a moot statement when one considers that even the most basic tools used by tribal people are technology). As a species, we humans celebrate our material creations more than any other species on the planet. We're always hearing about, waiting for, and craving the next best thing. One need simply look to the smartphone industry for a perfect example of this insatiable collective obsession with technology. This video clip does a pretty good job of lampooning people's obsession with the iPhone, arguably the single most hyped (and I'm inclined to say over-hyped) piece of communication-technology in the past 5 years. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FVkH9Hgvda4&feature=share. (I'm fully aware that, as an owner of a Samsung Galaxy S2, I'm every bit as guilty of the the same "crimes" against reality that iPhone users are.)

Of course, love of technology isn't a crime and I don't think that's what Virilio was trying to say. The main push of the entire book is just a call to wake up and be aware of how ever evolving technology and "real time" is changing our world. By making ourselves aware of this, we will be better able to prevent the shrinking of distances and time that have defined our reality up until this new era.

questions:

1) How do you think a conversation between Paul Virilio (who warns against our embrace of time-light) and Steve Jobs (who some could consider the "time-light zeitgeist) might play out?

2) Open Sky was originally published in 1995. Do you think it adequately assessed the condition of the world since then?

3) How does Virilio's cautionary tale in Open Sky compare to Turkle's in Alone Together?